Motivation is one of the hardest things I treat. It’s at the core of so many issues. Parents think their kid’s lack of motivation is laziness or a moral failing or just a phase. The research says something different.

Are there lazy kids? Oh, for sure. There are also cultural drivers like unchecked privilege. But for a majority of college-aged kiddos with a motivation issue, there may be more going on.

Before we get into the research, let’s talk about what I mean by motivation issues. I’m not talking about the morning after partying all night and not really feeling like studying for Monday’s test.

I’m talking about that ever-present feeling that the big things in life like a career, family, taking care of one’s body, relationships, …whatever you can imagine, just aren’t rewarding enough. There isn’t that internal drive. Future stuff just doesn’t seem important enough. Motivation issues and depression have a lot in common but not everyone that lacks drive is depressed. For example, I might take pleasure from lots of things like hanging out with friends or gaming but may not have much of a drive to go to class or apply for internships. For some, they never had that fire in their gut that pulls them forward. For others, they may have had head trauma or a significant event that significantly impacted their brain.

Speaking of brains, let’s go ahead and look at the neurological research. Motivation is not a psychological or moral issue – it’s a neurological issue that’s only recently been studied and understood.

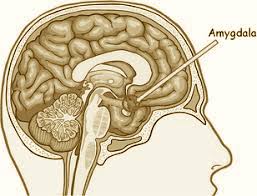

Our brains have an emotionally sensitive gatekeeper called the amygdala. When there’s low stress, the amygdala directs information to the prefrontal cortex (PFC). The PFC processes that information into long-term memory or immediate cognitive/emotional signal. We can either respond to it or ignore it.

Unfortunately, this response can’t happen when we experience a significant emotional state which blocks this flow of information and processing. Situations that trigger a sense of frustration, anger, or boredom are associated with high stress within the amygdala.

Unfortunately, this response can’t happen when we experience a significant emotional state which blocks this flow of information and processing. Situations that trigger a sense of frustration, anger, or boredom are associated with high stress within the amygdala.

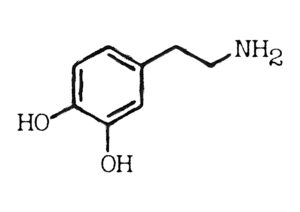

A recent study looked at the brains of both “motivated” and “unmotivated” participants. Researchers found that those who were willing to work hard for rewards had more dopamine which was found in the striatum and PFC, both of which are associated with motivation and reward.

With the “unmotivated” participants, however, dopamine was only found in the anterior insula which is associated with emotion and risk perception. Motivation levels are strongly related to the perceived difficulty of a task and the perceived rewards that come from its completion. When there are low rewards, the motivation to work through will be lower.

If the perceived difficulty of a task suddenly increases during a period of low motivation, motivation will drop further. This eventually leads to a downward spiral in motivation level unless we override it.

What to Do

Dr. Victor Harold Vroom, a business school professor at the Yale School of Management developed the Vroom’s expectancy theory which assumes that behavior results from conscious choices. Vroom also believed that individual factors such as personality, skills, knowledge, experience and abilities were factors in how we experience motivation. Finally, Vroom mentions three variables that contribute to increasing (or decreasing) motivation — expectancy, instrumentality, and valence.

Expectancy is having the right tools or skills. I think of this as a competency for a given task.

Instrumentality is the clear understanding of the relationship between performance/behavior and rewards/consequences.

Valence is the importance we place on an expected outcome. If something doesn’t matter to me, why would I invest time and resources into it?

Motivation Essentials

When the reward is greater, we tend to be more motivated. Makes sense but how can we achieve high motivation for those tedious or repetitive tasks that just are so mentally painful and boring?

Set SMART goals

For starters, think of EVERY goal being defined by the SMART definition – Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Time-sensitive. Another strategy is to make tasks less difficult by breaking them into smaller pieces. For example, if you’ve got a big test in a week that covers 5 chapters, schedule five study sessions for 90 min for each chapter. Don’t focus on the test, focus on the smallest “to-do” list item related to your studying. Need even smaller pieces? For each 90 min study session, assume you’ll take a 5 min break every 30 minutes or after a certain number of pages reviewed.

When possible, increase the rewards for completing a task. Maybe when you finish studying a chapter or two for the test you reward yourself by going to dinner with friends instead of ordering Jimmy Johns.

Basically, set achievable goals with stimulating rewards broken into small pieces. When you see the finish line, you’re more likely to keep running forward until you’ve reached it.

Train the brain

Besides setting SMART goals, we can also train our brains.

When we realize our brain’s fight/flight/freeze response is activated, saying to ourselves “I am angry” or “I’m sad” reinforces the threat response. Whenever we say to ourselves “I am…” we’re actually making a statement about identity as if it’s concrete and a fact. This implies the permanence of that emotion. Essentially you’re saying to yourself, “The emotion is who I am.” Instead, it’s healthier to characterize emotion as something that’s felt and temporary. If I said I am a skin burn after touching the stove, that seems kinda crazy. Instead, I would say I felt pain from getting burned. Saying, “I feel…” rather than “I am…” will result in a greater sense of control since we actually don’t control our feelings. That’s a simple way to train your brain.

There’s still a lot more to motivation than what I’ve covered here but for now this gives you a solid foundation. Whether you’re starting another semester or just graduated, use these techniques and information to make sure you keep moving your life forward.